183. Situational Awareness and Decision Making in Diving

|

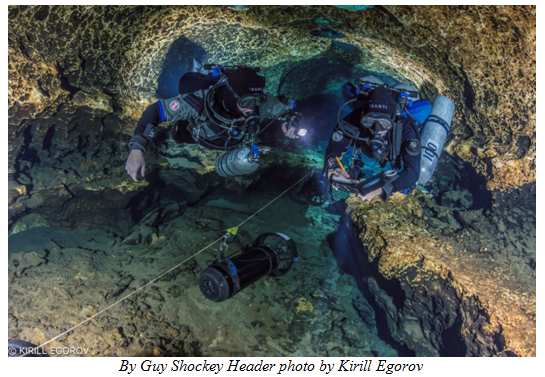

Situational awareness is critical to diving safety, right? But how much of your mental capacity should be devoted to situational monitoring, e.g., How deep am I? How much gas do I have? Where is my buddy? Where is my boat? More importantly, how does one develop that capacity? Here GUE Instructor Trainer Guy Shockey, who is also a human factors or non-technical skills instructor, explores the nature and importance of situational awareness, and what you can do to up your game. 1 April 2020 by Guy Shockey (*) - InDepth |

|

|

It is not surprising that given the nature of the activity and its heavy reliance on equipment, the majority of diving discussions focus on the “technological” side of diving which includes equipment, gases, decompression, etc. These discussions will assuredly still continue but over the last few years we have seen a renewed focus on what we refer to as “Human Factors” (HF) and their role in technical diving and diving in general. I for one am happy with this shift in emphasis; regardless of what equipment, gases or deco protocols you are using, HF is always a part of the equation. It strikes me as a bit odd that divers would spend hundreds and thousands of dollars trying to find the “perfect” bolt snap or retractor and ignore training the “human in the system”. |

|

This despite the knowledge that we can learn how to be better decision makers once we are aware of just what things influence our decision making. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter what gear configuration or equipment or gases we are using if we have no ability to make good decisions while diving. It doesn’t matter a lot what “make of vehicle” I drive, if I don’t make smart decisions while driving. Thankfully, there has been a sea change in this attitude and today, just about every diving conference, magazine or blog has started discussing Human Factors or non-technical skills (NTS). As an active GUE instructor, I have tried to stay current with this and include HF training in all my classes in some capacity. I believe HF becomes more important as the diver progresses in their technical training, and even more so if they make the shift to CCR diving. Regardless of the level of diving though, the one common feature of all divers is, as Human Factors coach, Gareth Lock writes, “the human in the system.” It seems only logical then that it would make sense to turn our attention onto the human diver.

Brain Capacity Human Factors includes many aspects of understanding our decision making process, however, I believe there is one aspect of HF and NTS training that is particularly relevant to every diver. The concept of “Situational Awareness” (SA) has been a buzzword for several years now, but only more recently have we started to talk about it in terms of HF and diving. Former Chief Scientist for the United States Air Force, engineer Mica Endsley has been one of the luminaries on the subject of situational awareness and defines it as “the perception of the elements in the environment within a volume of time and space, the comprehension of their meaning, and the projection of their status in the near future”. This is a simple yet powerful sentence and deserves more consideration. |

|

The new diver or a diver working at the limits of their capacity in a new training or diving environment has a limited amount of internal RAM (random access memory) or CPU (central processing unit) power to call on to make decisions. They are typically overwhelmed by a new environment that includes changes in sight (everything is closer), sound (it travels faster underwater), physical changes on the body (changes in drysuit or wetsuit pressure), temperature (usually colder), and the overwhelming knowledge that humans are using life support equipment to operate in a hostile environment. Within that environment we are expecting divers to also monitor depth, time, location, team, gas, etc. Then, if there is an emergency, we also expect them to react with precision and skill to solve the problem. And finally, our expectation is that we are doing all this for fun! |

|

|

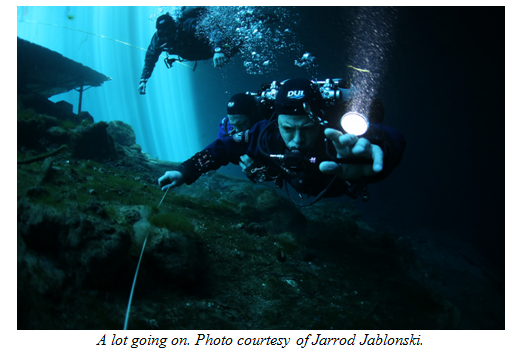

In summary, what we are expecting is for our divers to maintain a high level of situational awareness while operating in a hostile environment and maintaining enough capacity to deal with emergencies. Seems simple on paper right? It is readily apparent to any instructor that trying to monitor situational awareness is an overwhelming task for new divers or those divers pushing their training limits in a more advanced class. If the typical diver, who originally started diving to have fun, is using 75% of their capacity just to monitor their situational awareness (Where am I? How deep am I? How much gas do I have? Where is my buddy? Where is my boat? etc.) they only have 25% of their remaining capacity to do what they intended to do. The GUE philosophy is to train in such a fashion that we are able to switch this around in order to effectively dedicate 25% of our capacity to situational awareness monitoring and thus have 75% of our capacity to do what we came to do: have fun! There is an interesting yet critical corollary of this change in that when the first diver has an emergency they have only 25% of their capacity to dedicate to the problem. Contrast this to the trained GUE diver who has 75% of their capacity to help solve the emergency. |

|

Helper Muscle GUE classes are intended to help build your situational awareness while also developing fundamental skills for the level of training you are doing. Hence, it is not enough to just “do an S-drill” (check to see the long hose is not encumbered); we expect you to “do an S-drill” while also being aware of your position in the water column, proximity to the line, and awareness of your team mates. Consider SA as a “helper muscle” that we are developing while also working on the primary muscles. A good analogy might be using dumb bells for a chest press in a gym which requires you to stabilize the weight while also pushing it upward. This is quite different from doing a similar exercise on a machine where rails or tracks keep the load stabilized while you push or pull it. We carry this forward into our upper level classes where we require an even higher level of situational awareness such as tracking gas by time, etc. |

|

|

It is for this reason that I have become more and more convinced that situational awareness is quite possibly the most important skill that a diver must develop. As Endsley wrote, “As technology has evolved, many complex, dynamic systems have been created that tax the abilities of humans to act as effective timely decision makers when operating these systems”. As GUE has moved into the CCR training world, I believe we are seeing just how prophetic this statement from over 20 years ago actually is. SA is not just about “what is” but about “what will be”. In this aspect it requires the diver to first recognize the situation, then analyze what it means, and then project into the future how it will affect them. As the environment the diver is operating within continues to change, SA management becomes a complex and ever-changing exercise. Further, it stands to reason that poor SA will lead to poor decision making. |

|

|

Developing situational awareness will not happen without consciously working on it. One way you can do this on every dive is by making a conscious effort to anticipate your expected gas usage and then verifying it every five minutes. You can also work on anticipating the next step or waypoint in your dive and arriving there ready to perform whatever action you are expected to do. For example, if you are the one expected to deploy a surface marker buoy (SMB) at the 20 minute mark, then anticipate that and arrive at that time waypoint with the SMB out of your pocket and ready to deploy. If you are the one running a line from the shot line to the wreck, then arrive at the bottom of the shot line with the reel out and ready to go. These are only a few of the ways you can work on developing your situational awareness and you will find it gets easier over time. |

|

I tell my students that learning how to plan and complete a dive is not unlike learning a new dance where at first you may need numbered footprints on the ground telling you what foot to place and where. Then after practicing a few times, you can remove the footprints and then soon your footwork becomes second nature and you can concentrate on smiling at your dance partner as you prepare for the next “So You Think You Can Dance” tryout. Make every dive an effort to develop your situational awareness. It will pay off handsomely in terms of making you a more relaxed and confident diver. Before you know it, you will be doing things subconsciously that used to require significant RAM. This will make your diving more enjoyable and you will retain lots of capacity for problem solving, and worrying about your next dance lesson. |

| (*) Guy Shockey is a GUE instructor and trainer who is actively involved in mentoring the next generation of GUE divers. He started diving in 1982 in a cold mountain lake in Alberta, Canada. Since then he has logged somewhere close to 8,000 dives in most of the oceans of the world. He is a passionate technical diver with a particular interest in deeper ocean wreck diving. He is a former military officer and professional hunter with both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in political science. He is also an entrepreneur with several successful startup companies to his credit. |